(This text has been adapted from a presentation from August 2021 at EFACIS Prague, an Irish Studies Conference.)

The Irish Bungalow - based on the paper “Bungalow Bliss”? A Cultural Exploration of the Bungalow in Ireland by Emma McKeagney 2021.

Bungalows are everywhere. You see them in Ireland along most roads leading to towns and villages as well as in the outskirts of cities, in our suburbs. But they are also everywhere on a global scale too.

Anthony D. King, who wrote the most extensive exploration of the bungalow and its cultural significance, The Bungalow: The Production of a Global Culture (1984), explains that the bungalow is found “in every continent of the world… where every language has its own set of terms to describe different forms of dwelling, ‘bungalow’ has been accepted into the principal world languages and also many more.” (2) This pervasiveness of the bungalow in all global societies means that it provides “an excellent opportunity to investigate a large number of questions concerning our understanding of the built environment and the relation of that environment to society.” (1) Further study of the bungalow in the Irish landscape is therefore essential to understand Irish society’s relationship with the built environment, design, and the landscape it is built upon.

The fact that the bungalow is so pervasive makes it hard to study, almost like it’s reached a saturation point in society where it is now ignored. My paper aims to delve into the world of the bungalow in its specific Irish context. While there are many books, studies and texts on the Irish suburbs, Irish towns, Irish cities and Irish cottages there has been little to no sustained scholarship on the Irish bungalow.

SO where does the bungalow come from?

The bungalow comes from the colonial expansion of India from the 1600s and throughout the 1700s. The term comes from the Bengal region where the natives built huts out of thatch, bamboo and clay called ‘Banggolo’.

The colonists built temporary dwellings out of similar materials and termed them bungalows. These early dwellings became fixtures of writings on Indian military adventures and would have been translated back to Britain in this context. The first instance of the word in and English dictionary is in 1788 as a specifically Indian term. The word slowly merged into a word for new, modern and cheap homes in England.

In England, the bungalow emerged first as a second holiday-dwelling for the upper classes, as early as 1869. They were as a result of the accumulation of capital and the emerging notion of the ‘week-end’. They came about as bohemian spaces for the bourgeois who were protesting the ‘strains and stresses’ of industrial life. This also is where we see the country defined as somewhere used for pleasure for the first time as opposed to just agriculture. As they developed alongside new materials such as, timber, corrugate and asbestos, prefabrication became a new phenomenon as well as pattern books.

Pattern books of bungalows date back to as early as 1891, one called Bungalows and Country Residences by a man named R.A. Briggs. As these dwellings became cheaper they were available to the lower-middle and lower classes for seaside holiday homes.

Here it can be seen that the bungalow, in a few ways, emerges from colonial expansion. Not only is surplus capital accumulated through colonial endeavours, but cheap materials also become more available through global trade and the bungalow as a style itself is imported directly from colonial missions.

King also explains the American context of the bungalow. With some instances in the late 1800s, the bungalow form exploded in popularity in America in the early 1900s. First, like the English bungalow, it became popular as a second holiday-dwelling. The bungalow spread throughout North America, originally seen as a Californian entity. It was linked to the bohemian Arts and Crafts movement which originated in England and spread to America, criticizing the industrial revolution and promoting three principles of simplicity, harmony with nature and the promotion of craftmanship. “The bungalow was to become the incarnation of all three.” (King 134)

Once it proliferated in American culture, it became a global commodity and housing staple. Its original essence and unique culture remained central tenets to the bungalow, more than it just being one-storey, it is about ownership, the individual, entry to the housing market regardless of class and counter-urbanisation.

The bungalow, furthermore, stands for an evolution away from vernacular architecture towards a global cultural hegemony where the bungalow can exist and be recognised across the world. Its local tweaks may be different, but its origins are capitalist and global. This is essentially the main difference between the term ‘cottage’ and ‘bungalow’. The cottage is usually one-storey like the bungalow but the cottage implies inheritances from what is seen as vernacular; local materials, made by local people and inherited from local aesthetics. The bungalow, however, implies newness, design, style from elsewhere, cheapness and ease of building.

Due to Ireland’s place in the empire in the late 1800s and early 1900s, its struggle for independence, and its post-colonial stasis the bungalow has two trajectories in the Irish context. Firstly, it follows a similar inheritance to British and American contexts in the late nineteenth century and early 20th . There were bungalows built for the wealthy in counties in Ulster and around Dublin where there was more money and connections with the global economy.

Secondly, an explosion occurs in the 1970s coinciding with the State’s embrace of the global market economy. As happened with the British seaside bungalow, the bungalow proliferates in Ireland when a majority of people have more access to surplus wealth. This is also when the Irish State reduces the amount of social housing it is building in favour of neo-liberal policies. My dissertation goes into the housing policies which led to a dependency on self-building in rural areas as well as the cultural inclination for the Irish to remain embedded in rural areas. Padraic Kenna outlines the history of housing in the Republic of Ireland in his book Housing Law, Rights and Policy. The Land War of the late 1800s transformed the countryside of Ireland from a place where over 50,000 evictions took place in 1849 (26) (where just 13,000 landlords owned and controlled the land of Ireland (28)) to land being redistributed to over 316,000 holdings for small tenants after 1909. The Free State was created out of this clamorous movement and as Kenna explains, “after 1923, the work of the Land Commission in the new State was even more important in upholding the raison d’etre of the State itself.” (28)

While Paul Henry images are seen to be the kind of vernacular expectation for rural Ireland. The Congested Districts Board cottages would have been more common, and cheap bungalows were seen around the country as early as 1930. The bottom two bungalows are early examples in Ulster and Dublin. The bungalow became a common word used for newer houses, with all their mods and cons, whereas cottages implied an older model of dwelling, with no toilet, no light and no heating or cooker. While most people see the bungalow as a phenomenon dating to the 1970s and later, my study shows it had begun to proliferate well before this time.

Bungalow Bliss a book created by Jack Fitzsimons in 1971 has become a cult expression for the Irish bungalow of the 1970s. Bungalow Bliss was published by Jack Fitzsimons of County Meath in 1971. Fitzsimons background was within the County Engineers office as a draughtsman, and he put this book together upon suggestion by his wife, Anne who saw that he was having difficulty dealing with all of the drawings he was doing on an ad hoc basis for people building their own houses.

Throughout his own writings he insists the dearth of access to architects was the real reason why Bungalow Bliss was so popular. They sold their first bungalow to finance the books and handed the responsibility of binding to a Dublin man, Chris Kelly, who was relocating to Kells. Anne hand typed the books on an old typewriter they had at home. And the books were bound in a rudimentary fashion. When looking at this first edition in person the results of all these efforts can be seen in the materiality of the book which exudes a charm and sophistication which was perhaps not paralleled in its later editions. With only twenty plans, and most of the book made up of instructions on the process of building a house, it is clear how it quickly became a much-wanted commodity.

The book’s aims were to disseminate design to many, and it was successful in its cheapness. The book cost £1 to buy and copies of the plans cost £10. Further advice could be secured for just 9 pence. The book concisely goes through everything that is needed in the process of building a house; how to secure planning permission, the grants available, public utilities, loans, plumbing & drainage, electrics, heating, how to deal with contractors and tradesmen, furnishing, painting and decoration, maintenance, gardens and grounds and car garages. Even though Bungalow Bliss is often assumed to be just a pattern book, it goes further and aids people in creating a fully equipped and lived-in home.

Each edition of the book started with this quote telling people to get an architect if they could afford one, however he acknowledges that very few people could afford an architect. He explains to the reader how to think about their built environment like a designer, and how to craft it to individual preferences. He hands over the tools of a designer to the layman in the hope of elevating their living standards. In the way he describes space, it is clear that Fitzsimons is aware of the contortions domestic space must do in holding a family; a room for dinner can become a room for exercise, a living room for relaxation and reading can also contort to become a hub of entertainment for guests and extended family. This book not only describes how to build a house, it describes how best to arrange it in order for it to become a home, and therefore, is also a book which describes how best to live in space.

With this book, Fitzsimons’ intended to do more than merely hand out patterns for people to follow to the letter; his wish was to allow people access to design ideas, and the ability to tweak their home as they felt they would need. Later editions held information on the best way to site the bungalows, and attempted to further educate people on planning laws and theories. The book shows his in-depth understanding of house construction, but also his ability to translate it in a clear and comprehensible way. See for example, his hand-drawn map of a standard house’s plumbing. (Above.)

One of the major turning points for the conversation around bungalows in Ireland and the Bungalow Bliss books was a series of articles written by Frank McDonald in The Irish Times in 1987 entitled “Bungalow Blitz”. This play on the title of Jack Fitzsimons’ book vilified the pattern book claiming that it resulted in the destruction of the Irish landscape with specific emphasis on the west of Ireland.

The language McDonald uses is filled with disdain for the bungalows and their inhabitants. The bungalows are described as “showy” or “brash” as opposed to the traditional cottages which they replaced. At no point is there any real attempt to understand the decision to want to build or live in a bungalow other than an inherent “cultural bankruptcy” or a need to show that “they are there to be seen. ‘We have made it, and to hell with the rest of you.’” McDonald exudes a superiority over the western inhabitants of bungalows;

There is more than a touch of the Third World about the place in its chaos and disorder. The ruins of old cottages, if they are used at all, are used for storing hay or keeping cattle. Several houses, even some of the modern bungalows, are “landscaped” with scrap cars, piled on top of each other in the field. (A1)

McDonald makes his own position clear, and paints a horrific picture for the readers of the Irish Times, by his second instalment of his series, of their rural idyll destroyed;

Throughout the length and breadth of the country, rural areas are being destroyed relentlessly by this structural litter on the landscape – litter that can never be removed. And this cancer is so pervasive that for every private house built on a suburban housing estate, at least one other house is built in the middle of the countryside. If this was Eamon De Valera’s dream of a country “bright with cosy homesteads,” it has turned into a nightmare. Because what is happening, in effect, is that we are abandoning our towns and villages in favour of colonising the countryside. (McDonald Blight and the palazzi gombeeni effect 8)

McDonald distinguishes between those who are “urban-generated” and “of the countryside” arguing that the bungalow is a creation of the urban dweller moving outwards and “choos[ing] to live in a rural environment for status reasons or because they simply like the fresh air.” (8) This is a clear simplification of the phenomenon of the bungalow and also begs the question; What makes someone of the countryside? How do we categorize countryside, nature, town and the dwellers in and between in Ireland?

Dalkey, a monied suburb south of Dublin, was largely common, rural land up until the middle of the nineteenth century . Dalkey Commons had remained an untouched kind of idyll near Dublin up to the early nineteenth century. In 1840 it was described similarly to how the west is often described;

...from Dun Leary to the lands-end at Dalkey common, presented a nearly uniform character of wildness and solitude – healthy grounds, broken only by masses of granite rocks, and tufts of blossomy furze without culture, and except in the little walled villages of Bullock and Dalkey, almost uninhabited. (Clare 30)

The suburbs have been allowed to sprawl outwards from Dublin city into formerly common land. The creation of private holdings on the commons of Dalkey through a process of enclosure was contested at the time (Clare) yet it is now accepted as a normal fixture of the suburban landscape.

Dalkey Commons, Section of OS Map of Ireland, 1829-41

Dalkey Commons, with increased one-off housing, section of OS map, 1897-1913

When vilifying the proprietors of bungalows for building on land fairly purchased, it is never connected to the creation of more formal suburbs in Dublin or elsewhere. Perhaps a more fitting question about the bungalow is how to improve our collective relationship with land ownership and building in the natural environment no matter where in the country one is building. As Dominic Stevens has explored, instead of focussing on whether one should build in rural Ireland, the question needs to be inverted towards how we should build in rural Ireland.

If the Irish landscape of the future is to be designed, we must thus decide what function we wish to assign to it. What is rural Ireland for? For looking at, an example of natural beauty to be preserved as much as is possible in its present state? For farming and the production of food? For the production of energy? A place to live, where community can happen outside centres of population? What are our priorities? (Stevens 74)

My dissertation aims to tease out the debate around the bungalow, attempting to answer the question. Why is the bungalow so problematic?

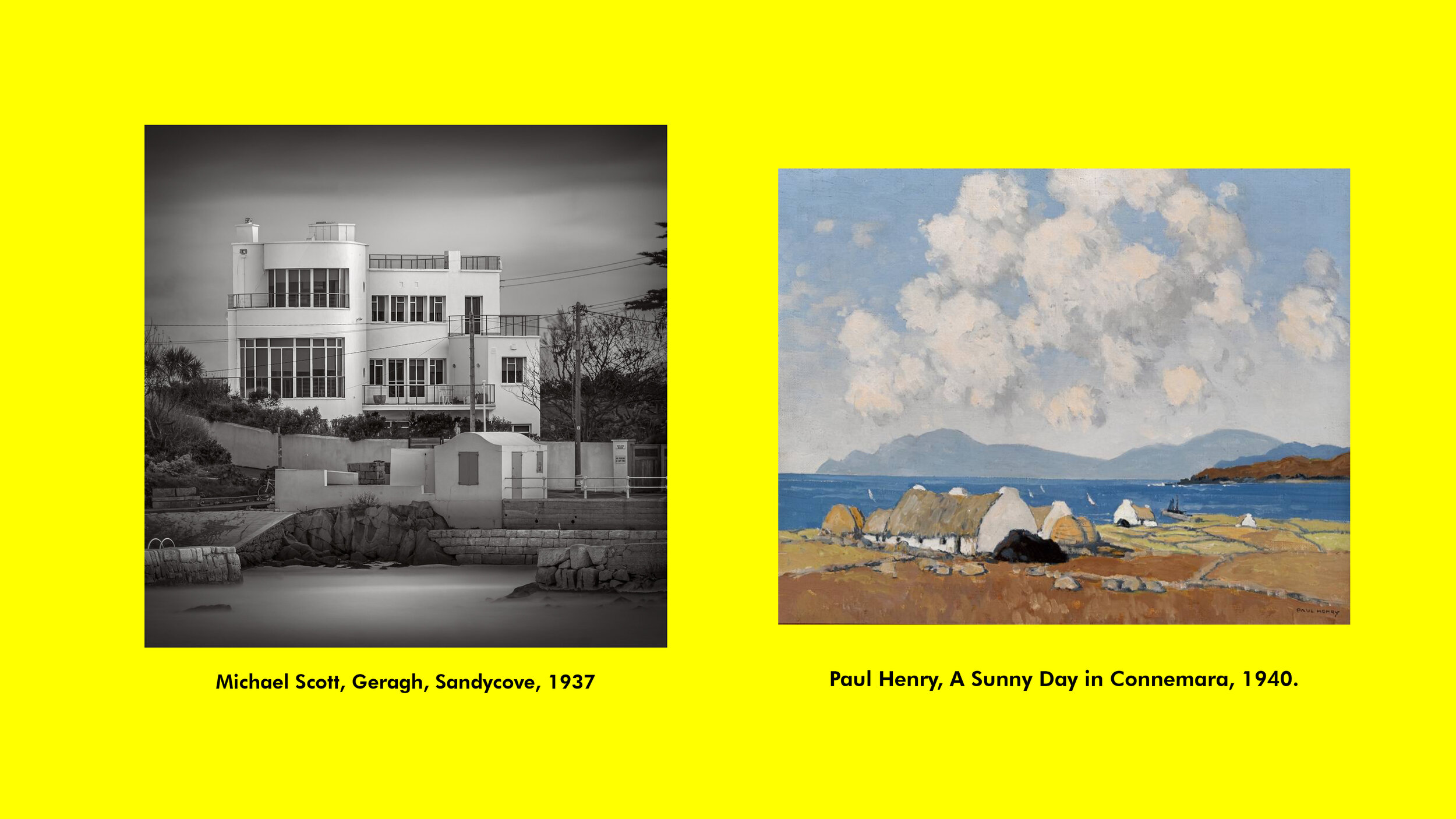

What my third chapter explores is the dynamic of design in Ireland. These two images (above) side by side are striking. The building on the left was built in a wealthy suburb of Dublin three years before the painting on the right was painted.

Design, my thesis ascertains, was highly privatised and created a divisionary dynamic in the republic, where the rural west was expected to remain crystallised in the past; and the east was allowed to develop. To locate the main issue of the bungalow as an issue for the eye of the beholder is to ignore the bungalow dweller, their life, and their choice to build and live in the countryside. McMeniman & Sheridan (2019) outline the theories of the ‘Rural Gaze’ or the ‘Tourist Gaze’ in relation to vernacular architecture. The Rural Gaze acts in ways that distance rurality from globalisation and capital networks as well as “obscuring the recognition of problems such as poverty and deprivation in rural areas.” (799) This denial of networks of class and poverty within rural areas by the visitor acts to obscure the reality that the bungalow may be all the local community can afford and that the vernacular cottage “ironically today only the wealthy can afford to renovate and maintain.” (799)

The bungalow emerges at different time trajectories for these divided groups in Irish society. In the east and north of the island earlier in the century, and in the west of the island from the 1970s. Those who criticize the bungalow’s place in the west of Ireland may well be writing from a bungalow in the east, yet on more formalised suburbs or land which was enclosed and converted from common land to holdings in the nineteenth century instead of the twentieth. The bungalow materializes where excess capital allows a person to build their own home with materials available on the global market as opposed to local materials. Yet excess capital in society does not necessarily mean that people acquire more wealth equally across the population. People work more, away from the home, which means there is less time to work with one’s surroundings and to create their own dwellings as would have been the case in the creation of vernacular architecture. Recent literature (McMenamin & Sheridan 2012, 2019) has challenged existing notions of vernacular architecture, where intentions of the vernacular builder are flattened and seen as simplistic and picturesque. McMenamin and Sheridan support literature that analyses vernacular architecture for its ‘Utilitarian-Landscape’ approach which is;

A way of understanding vernacular environments in terms of the resourceful use of landscape elements by vernacular creator-agents for imperative utilitarian purpose (spatial definition, shelter, containment, access, agricultural function). (McMenamin & Sheridan Interpreting Vernacular Space 791)

The emphasis on the creator of the vernacular architecture as agentic and working with the landscape implies more design strategy within vernacular architecture than is often prescribed. To look at vernacular architecture beyond typological categories towards an agentic strategic based design layout is something “which contemporary place-making might indeed take some instruction.” (795) This newer approach to vernacular architecture most importantly stresses vernacular dwellings as “sites of human ingenuity that reveal the agency, resourcefulness and adaptability of their creators.” (McMenamin & Sheridan Utility & Aesthetics of landscape 46) Design in a globalised world becomes a privatised commodity but it has always existed as how humans interact with materials and our surroundings;

Design is the most human thing about us. Design is what makes the human. It is the basis of social life, from the earliest artefacts to today’s ongoing exponential expansion of human capability. The human radiates design in all directions. (Colomina & Wigley 12)

In the creation of vernacular architecture, individuals had the time to design their surroundings in relation to the landscape. When this becomes a privatised trade that must be purchased, design becomes out of reach to many and commodified. The bungalow becomes a market-based solution to design as an expensive commodity, and the long history of bungalow pattern books is a direct result of colonial expansion, accumulation and the need for people to house themselves on the market’s terms.

In my last chapter, I compare the Irish design dynamic to the Swedish, where design is written into their housing and welfare policies. When design goes unacknowledged by the State, or as housing provision becomes privatised; individuals must seek out design themselves. Bungalow Bliss, as vociferated as it is, provided this design guidance to people when they needed it. Furthermore, an important point when analyzing this study’s comparison with Swedish design dynamics is Ireland’s post-colonial position. This has created an anti-authoritarian streak in the population where, combined with existing land tenure anxieties, these traits combine to create an anti-planning rhetoric. This may be one precise reason why Bungalow Bliss was so successful. Although it prescribed a kind of standard type of housing to many it was delivered on the private market by an individual rather than the state. This allowed consumers to feel they had chosen something for themselves rather than having a particular design ideology inflicted on them by state officials far away. If policymakers were to consider seriously the success of Bungalow Bliss they could blend its merits, such as how it teaches and disseminates domestic design ideals, with engaged policy creation as Scott et. al (2005) have recommended, to create a more holistic design ideology across the population which is publicly led and accessible to all. However, without an overriding unified housing policy approach and a dependency on the private market to provide housing, a dominant design ideology will always be a challenge to implement. In any case, much can be learned from how Bungalow Bliss was disseminated and how successful it was. In a time where the State is scrambling to build enough homes for the population, alternative ways of design and building dissemination are vital. Bungalow Bliss may not have been perfect but much can be learned from its successes.

Ultimately, the bungalow as a dwelling-type is not going to disappear in the Irish landscape, yet it has already started to mutate. As a new generation of bungalows begins to appear and as bungalows from the Bungalow Bliss era are slowly becoming modernised and improved (See Below) the opportunity to study bungalows from this vital era of Jack Fitzsimons and prior will diminish. This timely study takes the bungalow, the unwanted child in the Irish landscape, and allows it to be reassessed as a valid spatial form worth studying and learning from.

Thank you for reading. References are below. To read the full paper email me. I will be carrying out a photography project across the island of Ireland from November 2021. If you would like to volunteer to have your bungalow photographed please email emmamckeagney@gmail.com with a location and image of your bungalow.

References

Primary

County Archives, Donegal. “Housing / Labourers’ Cottages.” Donegal County Council, www.donegalcoco.ie/culture/archives/countyarchivescollection/donegalcountycouncil/.

Fitzsimons, Jack. Bungalow Bliss. Kells Publishing Co. Ltd., First Ed. 1971.

--Bungalow Bliss.Kells Publishing Co. Ltd., Seventh Ed. 1981.

-- Bungalow Bliss. Kells Publishing Co. Ltd., Twelfth Ed. 1998.

Irish Architectural Archives, TJ Cullen Collection, Bungalow at Shanganagh, 85/74 R.161

-- Einenelly, Wicklow, 85/74 R. 149

--Dictionary of Irish Architects 1720-1940, https://www.dia.ie/

Ordnance Survey Ireland. “Historical Ordnance Survey Maps of Ireland.” Ordnance Survey Ireland, 1832-1914, osi.ie/.

Whyte's. “A Sunny DAY, CONNEMARA, C.1940 by Paul Henry Rha (1876-1958) Rha (1876-1958) at WHYTE'S Auctions: Whyte's - Irish Art & Collectibles.” Whyte's, www.whytes.ie/art/a-sunny-day-connemara-c1940/169707/?SearchString=&LotNumSearch=18&GuidePrice=&OrderBy=&ArtistID=&ArrangeBy=list&NumPerPage=15&offset=0.

“1937 – Geragh, Sandycove, Dun LAOGHAIRE, Co. Dublin.” Archiseek, 22 Nov. 2017, www.archiseek.com/2010/1937-geragh-sandycove-dun-laoghaire-co-dublin/.

Secondary

Clare, Liam., Enclosing the commons; Dalkey, the Sugar Loaves and Bray, 1820-1870, Four Courts Press, 2004.

Colomina, Beatriz. And Mark Wigley. Are We Human?: Notes on the archaeology of design, Lars Müller Publishers, 2016.

Fitzsimons, Jack. Bungalow Bashing. Kells Publishing Company, 1990.

-- Bungalow Bliss Bias. Kells Publishing Co Ltd, 2019.

Glassie, Henry. Vernacular Architecture. Material Culture; Indiana University Press, 2000.

Hearne, Rory. Housing Shock the Irish Housing Crisis and How to Solve It. Policy Press, 2020.

Kenna, Padraic. Housing Law, Rights and Policy. Clarus, 2011.

King, Anthony D. The Bungalow: The Production of a Global Culture. Routledge, 1984.

McDonald, Frank. “Bungalow Blitz.” The Irish Times, 12 Sept. 1987, pp. A1–A5.

---“Blight and the Palazzi Gombeeni Effect: Bungalow Blitz.” The Irish Times, 14 Sept. 1987, p. 8

--- “The Ribbon That's Strangling Ireland.” The Irish Times, 15 Sept. 1987, p. 13.

McGarry, Marion. Irish Cottage: History, Culture and Design. Orpen Press, 2017.

McMenamin, Deirdre, and Dougal Sheridan. “The utility and aesthetics of landscape: a case study of Irish vernacular architecture.” In: Journal of Landscape Architecture, vol. 7, no.2, 2012, pp. 46-53.

---“Interpreting Vernacular Space in Ireland: A New Sensibility.” Landscape Research, vol. 44, no. 7, 2019, pp. 787–803.

Murphy, Keith M.. Swedish Design: An Ethnography, Cornell University Press, 2015. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nuig/detail.action?docID=3138739.

O'Reilly, Barry. Living Under Thatch. Mercier Press, 2004.

---“‘A SHOWER FROM THE SKY’: LEGITIMATING VERNACULAR BUILT ENVIRONMENTS IN IRELAND.” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, vol. 28, no. 1, 2016, p. 64.

Pfeiffer, Walter, and Maura. Shaffrey. The Irish Town – An Approach to Survival, O’Brien Press, 1975.

---Irish Cottages. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1990.

Scott, Mark, et al. “'Design Matters': Understanding Professional, Community and Consumer Preferences for the Design of Rural Housing in the Irish Landscape.” Town Planning Review, vol. 84, no. 3, 2013, pp. 337–370.

Scott, Mark. “Housing Conflicts in the Irish Countryside: Uses and Abuses of Postcolonial Narratives.” Landscape Research, vol. 37, no. 1, 2012, pp. 91–114.

Stevens, Dominic. “What Becomes of Rural Ireland?” Irish Review (Cork, Ireland), no. 31, 2004, pp. 74–78.